TERMODINAMIKA

Disusun Ulang Oleh:

Arip Nurahman

Pendidikan Fisika, FPMIPA. Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia

&

Follower Open Course Ware at MIT-Harvard University. Cambridge. USA.

Materi kuliah termodinamika ini disusun dari hasil perkuliahan di departemen fisika FPMIPA Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia dengan Dosen:

1. Bpk. Drs. Saeful Karim, M.Si.

2. Bpk. Insan Arif Hidayat, S.Pd., M.Si.

Dan dengan sumber bahan bacaan lebih lanjut dari :

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Thermodynamics

Professor Z. S. Spakovszk, Ph.D.

Office: 31-265

Phone: 617-253-2196

Email: zolti@mit.edu

Aero-Astro Web: http://mit.edu/aeroastro/people/spakovszky

Gas Turbine Laboratory: home

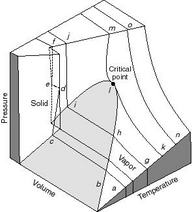

Changes in the state of a system are produced by interactions with the environment through heat and work, which are two different modes of energy transfer. During these interactions, equilibrium (a static or quasi-static process) is necessary for the equations that relate system properties to one-another to be valid.

1.3.1 Heat

Heat is energy

transferred due to temperature differences only.

- Heat transfer can alter system states;

- Bodies don't ``contain'' heat; heat is identified as it comes across system boundaries;

- The amount of heat needed to go from one state to another is path dependent;

- Adiabatic processes are ones in which no heat is transferred.

1.3.2 Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics

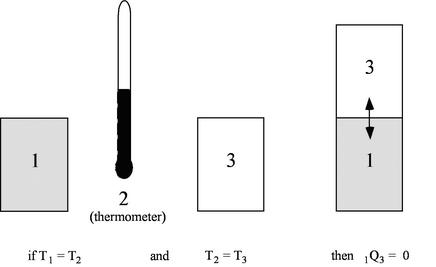

With the material we have discussed so far, we are now in a position to describe the Zeroth Law. Like the other laws of thermodynamics we will see, the Zeroth Law is based on observation. We start with two such observations:

- If two bodies are in contact through a thermally-conducting boundary for a sufficiently long time, no further observable changes take place; thermal equilibrium is said to prevail.

- Two systems which are individually in thermal equilibrium with a third are in thermal equilibrium with each other; all three systems have the same value of the property called temperature.

These closely connected ideas of temperature and thermal equilibrium are expressed formally in the ``Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics:''

Zeroth Law: There exists for every thermodynamic system in equilibrium a property called temperature. Equality of temperature is a necessary and sufficient condition for thermal equilibrium.

The Zeroth Law thus defines a property (temperature) and describes its behavior1.3.

Note that this law is true regardless of how we measure the property temperature. (Other relationships we work with will typically require an absolute scale, so in these notes we use either the Kelvin  or Rankine

or Rankine  scales. Temperature scales will be discussed further in Section 6.2.) The zeroth law is depicted schematically in Figure 1.8.

scales. Temperature scales will be discussed further in Section 6.2.) The zeroth law is depicted schematically in Figure 1.8.

Figure 1.8: The zeroth law schematically | |

[VW, S & B: 4.1-4.6]

Section 1.3.1 stated that heat is a way of changing the energy of a system by virtue of a temperature difference only. Any other means for changing the energy of a system is called work. We can have push-pull work (e.g. in a piston-cylinder, lifting a weight), electric and magnetic work (e.g. an electric motor), chemical work, surface tension work, elastic work, etc. In defining work, we focus on the effects that the system (e.g. an engine) has on its surroundings. Thus we define work as being positive when the system does work on the surroundings (energy leaves the system). If work is done on the system (energy added to the system), the work is negative.

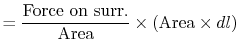

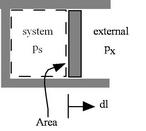

Consider a simple compressible substance, for example, a gas (the system), exerting a force on the surroundings via a piston, which moves through some distance,  (Figure 1.9). The work done on the surroundings,

(Figure 1.9). The work done on the surroundings,  , is

, is

Why is the pressure

instead of

? Consider

(vacuum).

No work is done

on the surroundings even though

changes and the system volume changes.

Use of  instead of

instead of  is often inconvenient because it is usually the state of the system that we are interested in. The external pressure can only be related to the system pressure if

is often inconvenient because it is usually the state of the system that we are interested in. The external pressure can only be related to the system pressure if  . For this to occur, there cannot be any friction, and the process must also be slow enough so that pressure differences due to accelerations are not significant. In other words, we require a ``quasi-static'' process,

. For this to occur, there cannot be any friction, and the process must also be slow enough so that pressure differences due to accelerations are not significant. In other words, we require a ``quasi-static'' process,  . Consider

. Consider  .

.

and the work done by the system is the same as the work done on the surroundings.

Under these conditions, we say that the process is ``reversible.'' The conditions for reversibility are that:

- If the process is reversed, the system and the surroundings will be returned to the original states.

- To reverse the process we need to apply only an infinitesimal

. A reversible process can be altered in direction by infinitesimal changes in the external conditions (see Van Ness, Chapter 2).

. A reversible process can be altered in direction by infinitesimal changes in the external conditions (see Van Ness, Chapter 2).

Remember this result, that we can only relate work done on surroundings to system pressure for quasi-static (or reversible) processes. In the case of a ``free expansion,'' where  (vacuum),

(vacuum),  is not related to

is not related to  (and thus, not related to the work) because the system is not in equilibrium.

(and thus, not related to the work) because the system is not in equilibrium.

We can write the above expression for work done by the system in terms of the specific volume,  ,

,

where

is the mass of the system. Note that if the system volume

expands against a force, work is done

by the system. If the system volume

contracts under a force, work is done

on the system.

Figure 1.9: A closed system (dashed box) against a piston, which moves into the surroundings | |

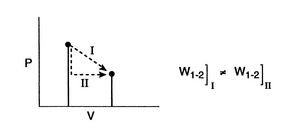

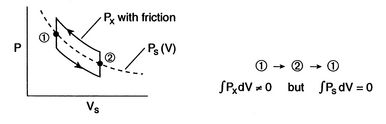

Figure 1.10: Work during an irreversible process

| |

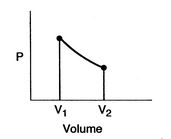

For simple compressible substances in reversible processes, the work done can be represented as the area under a curve in a pressure-volume diagram, as in Figure 1.11(a).

Key points to note are the following:

- Properties only depend on states, but work is path dependent (depends on the path taken between states); therefore work is not a property, and not a state variable.

- When we say

, the work between states 1 and 2, we need to specify the path.

, the work between states 1 and 2, we need to specify the path. - For irreversible (non-reversible) processes, we cannot use

; either the work must be given or it must be found by another method.

; either the work must be given or it must be found by another method.

Muddy Points

How do we know when work is done? (MP 1.3)

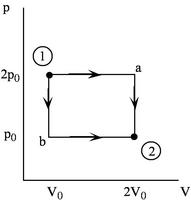

Consider Figure 1.12, which shows a system undergoing quasi-static processes for which we can calculate work interactions as  .

.

Figure 1.12: Simple processes | |

Along Path a:

Along Path b:

Practice Questions

Given a piston filled with air, ice, a bunsen burner, and a stack of small weights, describe

- how you would use these to move along either path a or path b above, and

- how you would physically know the work is different along each path.

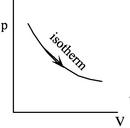

Consider the quasi-static, isothermal expansion of a thermally ideal gas from  ,

,  to

to  ,

,  , as shown in Figure 1.13. To find the work we must know the path. Is it specified? Yes, the path is specified as isothermal.

, as shown in Figure 1.13. To find the work we must know the path. Is it specified? Yes, the path is specified as isothermal.

Figure 1.13: Quasi-static, isothermal expansion of an ideal gas | |

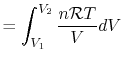

The equation of state for a thermally ideal gas is

where

is the number of moles,

is the Universal gas constant, and

is the total system volume. We write the work as above, substituting the ideal gas equation of state,

also for

,

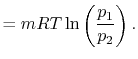

, so the work done by the system is

or in terms of the specific volume and the system mass,

We can have one, the other, or both: it depends on what crosses the system boundary (and thus, on how we define our system). For example consider a resistor that is heating a volume of water (Figure 1.14):

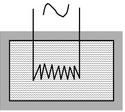

Figure 1.14: A resistor heating water | |

- If the water is the system, then the state of the system will be changed by heat transferred from the resistor.

- If the system is the water and the resistor combined, then the state of the system will be changed by electrical work.

Ucapan Terima Kasih:

Kepada Para Dosen di MIT dan Dosen Fisika FPMIPA Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia

Semoga Bermanfaat

![]() , the relations between the two quantities are:

, the relations between the two quantities are: ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() .

.  []

[]  []

[]

[Work depends on path]

[Work depends on path]